A monument to Vladimir Lenin, USSR, 1991 ©James Rodgers

‘DO YOU KNOW WHAT THE USSR WAS?’ asked the Ukrainian I had got talking to in London.

The USSR was many things to me — although I think it has taken a quarter of a century for me fully to understand something of what it was to others.

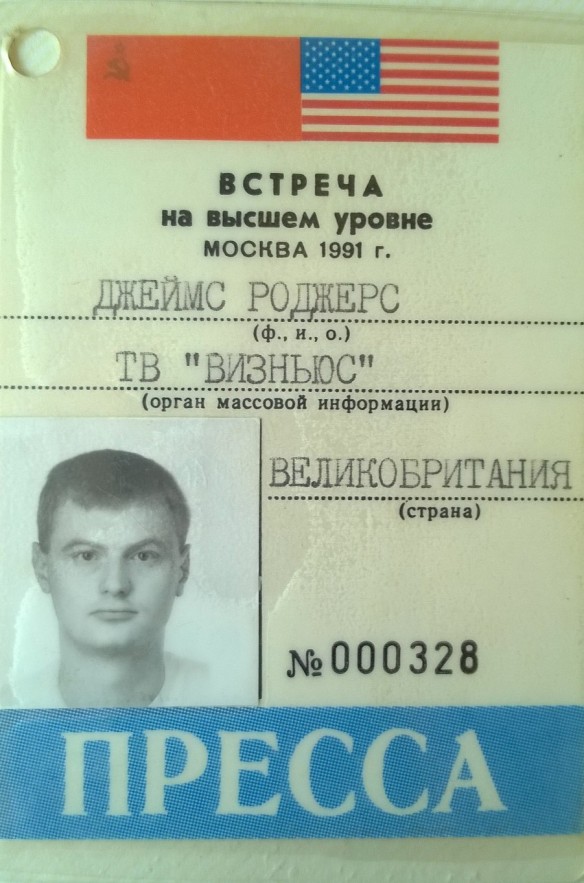

‘Bliss it was in that dawn to be alive/ But to be young was very heaven!’ wrote Wordsworth in ‘The French Revolution as It Appeared to Enthusiasts at Its Commencement’. That is how it felt to me to be in Moscow in 1991. I was in my 20s, and on my first foreign assignment as a TV producer, for the Visnews agency.

Russia’s post-Soviet revolution was ‘at its commencement’. For someone of my generation, who had spent their teenage years worrying whether the acceleration of the nuclear arms race in Europe was going to lead to conflict, the end of the Cold War between East and West was indeed blissful. The excitement of being on assignment in Moscow as a young journalist ‘was very heaven’. The world as I had known it all my life was changing forever, and I was there to see it.

What I — and the other young western journalists I met, and who were in some cases to become lifelong friends — saw that summer seemed good. Especially in the Soviet capital, we saw a population enthusiastic for change — brave enough, when the time came, to stand with sticks against tanks to defend it. They faced down a coup attempt by hardliners in August 1991 . Later that year, and 25 years ago this month, the Soviet Union formally ceased to exist. Back in London, I was in the newsroom on Christmas Day when Mikhail Gorbachev went on air in Moscow to resign, and the red flag was lowered from the Kremlin.

The Kremlin, summer 1991, with the Red flag of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics flying. © James Rodgers

For some Cold Warriors in the west, that was victory. For one prominent American academic, this was — absurdly, it is now clear — the ‘end of history’. For those of us who spend a lot of time reporting from Russia in the 1990s, it came to be something else: the beginning of an age of great hardship, uncertainty, and humiliation for millions of people in Russia, and other parts of the former USSR.

‘We keep on failing to understand the nature of the trauma that hit all Russians in 1991,’ Sir Rodric Braithwaite, the last British Ambassador to the USSR, told an audience at Chatham House 20 years later. Policy makers did not understand well the possible political consequences of that trauma either — at least until it was too late.

For it was in those days that the wrath of post-Soviet Russia was being nursed. It came to adulthood in the annexation of Ukraine, and, on the wider global stage, in the Middle East. The end of history mindset seemed to have prevailed among policy makers, too — again until it was too late. When relations with Russia turned bad, there were not enough people who understood why. ‘What’s really lacking in all these theatres is sufficient people who are deep experts on the language and the region to actually produce the options to ministers,’ complained Rory Stewart, then Chair of the House of Commons Defence Select Committee, in a 2014 interview with Prospect Magazine , as Russia cemented its hold over Ukraine.

Experts: in 2014, a senior Conservative politician said they were lacking; in 2016, another, Michael Gove, said Britain had ‘had enough’ of them.

Many disagreed — but enough were persuaded to accept the case made by Mr Gove and his fellow ‘Leave’ campaign leaders that Britain should leave the European Union.

That is one of the ways in which 2016 has helped me understand 1991. Now, in middle age, I have a perspective on how it must have felt for Russians in their 40s and 50s to see their country go to hell, taking with it all they had known.

This year, it has been the turn of my country to have a revolution — for that is what ‘Brexit’ is — and head off in an unknown direction. Not even those who most fervently sought this turn of events can claim that it has been adequately prepared for.

As a foreign correspondent in the 1990s and 2000s, I saw other people’s political systems fall apart. Both in the former USSR, and in the Middle East, this led on occasion to wars which cost countless thousands of lives. There is no prospect now of war in Western Europe, although that was the way we chose for centuries to settle our disputes. It is not simply coincidence that the era of the European Union has also been an age of peace.

The signs of other times are still there to see. As a frequent visitor to both Scotland and Denmark, my seaside walks lead me past Second World War fortifications scarring the beaches on the North Sea coast.

World War Two defences on the coast of East Lothian, Scotland, October 2016 ©James Rodgers

Will Europe ever be as divided again in my lifetime? As Christopher Clark wrote in the introduction to his excellent 2014 book The Sleepwalkers: How Europe went to War in 1914, ‘what must strike any twenty-first-century reader who follows the course of the summer crisis of 1914 is its raw modernity.’ He continued, ‘Since the end of the Cold War, a system of global bipolar stability has made way for a more complex and unpredictable array of forces.’

That’s why we need good journalism. Those of us western journalists who lived in Russia in the 1990s understood very well the reasons for Vladimir Putin’s rise to power (I wrote about this at greater length in a recent piece for The Conversation).

So, yes, I did know the USSR. A quarter of a century later, I know this, too: like the USSR, nothing lasts forever. Blissful dawns do not necessarily lead to sunny afternoons, or peaceful evenings. The demagogues who have tasted victory in 2016’s tumult would do well to remember that.